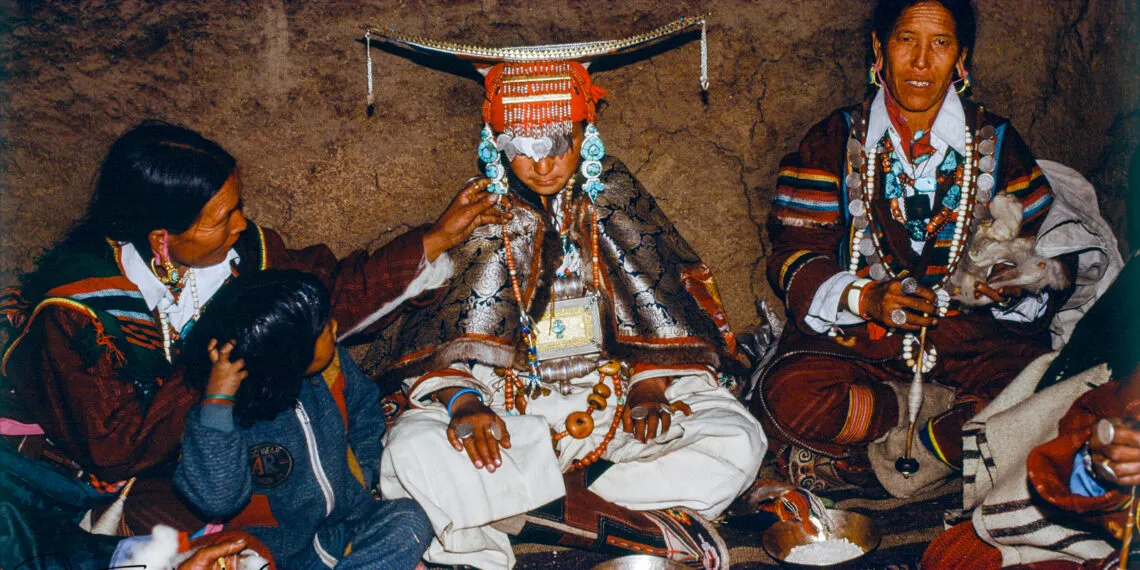

What if marriage wasn’t about love but survival? In the isolated Himalayan district of Humla, polyandry—the practice of a woman marrying more than one husband—remains common as a means of surviving the harsh environment.

Also, a familiar theme in Hindu mythology, polyandry for the people of Humla is not about preference but rather a tradition passed down through generations. The Nyinba, an ethnic group that migrated from Tibet several centuries ago, practice this marriage.

These communities have adapted to environments where arable land is scarce and the landscape is challenging. In this respect, polyandry is an effective way of maintaining the large ancestral territories for the heirs and avoiding their division upon inheritance.

Sharing is Caring?

Let’s assume that there is a family which has three sons. Rather than partitioning the family land, which would make it unprofitable, the brothers are polygamous and have one wife in common. This arrangement not only consolidates the family’s total available resources but also their efforts to manage the livestock, fields and homes.

In polyandrous households, the wife’s sexual rights are typically age-determined, with younger brothers only having access in the absence of older siblings.

In the words of Maila Dai, a trader from Bargaun village, “It is insurance for the wife.” If one husband is out or incapacitated, there will always be another to take care of her.”

Life in Humla requires one to be innovative in the way they get by. Therefore, farming, cattle rearing and trading form the basis of families’ income. Since one or at most two male partners in each marriage are usually away in trade or herding, multiple partners act as insurance for someone to stay back to tend to the household and family needs.

It helps in minimising or avoiding financial and labour costs that may be channelled towards something else. The siblings contribute to the efforts in achieving the higher goals by systematically organising the insufficient resources.

“It saves money and makes running a family easier.” – an elder of the Lama community. In monogamous households, the wealth could go separate ways since no two households are likely to be recognised as one family, while polyandrous families work as one unit, enabling them to thrive in a place where survival is a day-by-day struggle.

This practice of marriage also reduces rivalry over the inheritance of ancestral wealth and property and, at the same time, ensures that the siblings are closely related. This means that for women, the system provides safety because, with several males, the risks of being left or being left financially strained are low.

In the confined society of Humla, these marriages reflect cooperation and commonality. They portray a collective culture whereby the welfare of the family unit supersedes personal wants and needs.

Representation in Media

These interesting beliefs and values have captured the interest of writers and directors. In Shambhala, filmed in the remote Dolpo region, the movie follows the journey of Pema, who is married to Tashi but also shares a bond with her monk brother-in-law, Karma.

When Tashi leaves for a trip to Lhasa, Pema discovers she is pregnant, and the legitimacy of her child is questioned. This sparks a journey of self-discovery as Pema sets out to find Tashi, navigating not only the physical terrain but also the complexities of her identity.

Beyond Shambhala, documentaries like Himalaya: On the Path to the Sky offer a closer look at polyandry’s role in communities where it helps sustain families and preserve ancestral lands.

Challenges of Modern Times

While polyandry has remained beneficial in Humla, its future remains uncertain. Younger generations are questioning its relevance since education and migration opportunities are available to them. Modernisation and increasing population density present different ideologies and approaches to work and farming that may seem contradictory to traditional ideas.

Furthermore, legal and cultural systems in Nepal do not always permit polyandry because they are premised on hegemonic patriarchal structures. This poses certain problems for families who are still involved in this process, and they do not know how to go around other modern legal systems.

Although on the verge of decline, the polyandry culture in Humla is a testament to human adaptability and resilience. As we reflect on this tradition, let’s remember that marriage in Humla is more than a personal bond; it is a communal survival effort.

Pratikshya Bhatta is a junior editor for Nepal Connect.