A dialogue on adaptation, collaboration, and survival in a rapidly changing mountain region

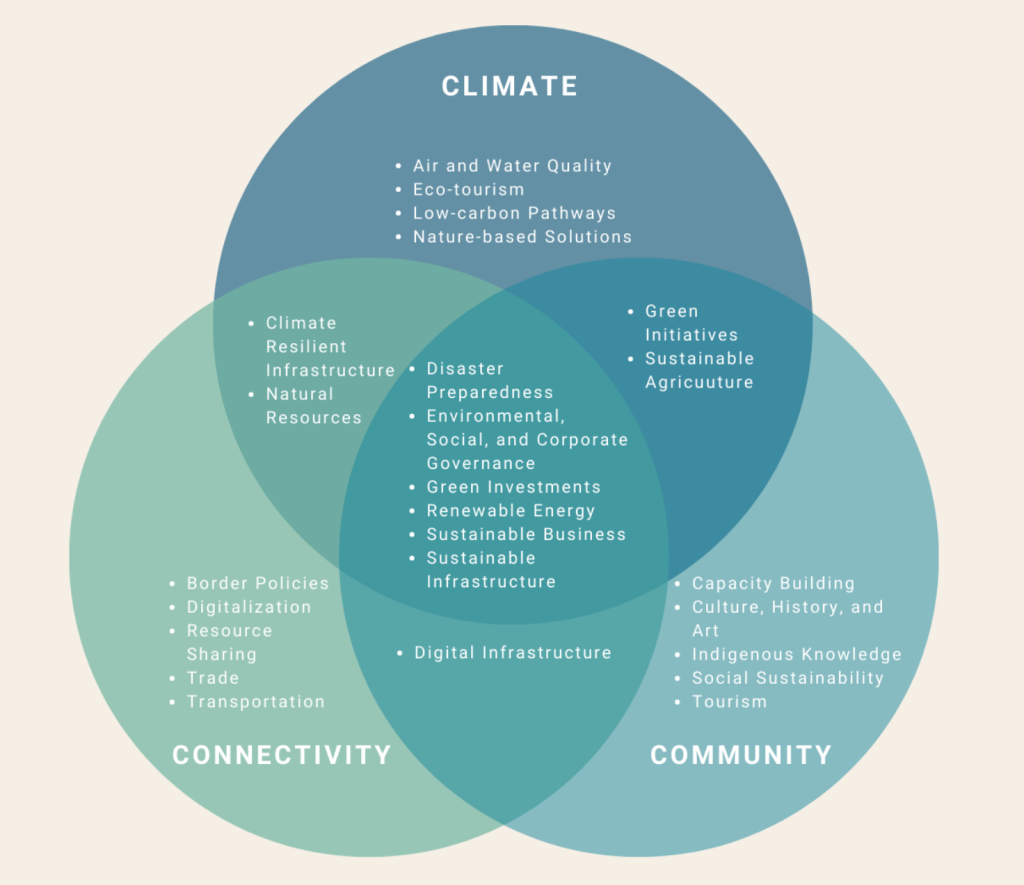

The second edition of the Himalayan Future Forum, held in Kathmandu on 6 February, featured a series of panel discussions on major issues in the region, loosely grouped under the motto ‘Climate, Connectivity, and Community’.

Geopolitics, (in)stability, climate change and migration featured prominently throughout the day, across panels, speeches, and discussions on probable causes and potential solutions.

The Vulnerability of Their Birthplace

In her opening speech, the EU ambassador, Veronique Lorenzo, stressed the region’s strategic importance and outlined concerns about the dangers posed by a shift towards regional hegemony for a few superstates. Economic integration, growing mutual trust, and security cooperation should strengthen and stabilise the Himalayan region.

Professor Mahendra P. Lama outlined the harsh consequences of changing weather patterns: less snow, more rain, hundreds of rapidly expanding glacial lakes, some in a critical state, volatile river behaviour, damage to hydropower plants, downstream flooding, landslides, and alternating periods of drought and sudden wildfires.

He stressed that seasonal confusion is a trap for mountain communities. They do not cause the problem but bear the brunt, victimised by the vulnerability of their birthplace. “They are the first to suffer and the last to get help.” What was once a playground has become a disaster area for adults.

Connectivity is crucial for identifying effective counter-policies. The region may be characterised by its ‘geography of borders’. Open ‘soft’ borders offer opportunities for economic and social interaction, while existing ‘hard’ borders may throw a spanner in the works.

The Himalayas and their southern flanks form a patchwork of neighbouring communities. Keeping corridors open and seeking collaboration within the framework of nature management, with an open eye for proven traditional land management practices and new technology, is desirable, or rather a must.

Mahendra Shrestha, an insurance expert, noted that natural disasters were once perceived as ‘acts of God,’ while the impact of climate change must be recognised as a logical consequence of quietly compounding threats to households and enterprises. Without a safety net, a flash flood or a landslide becomes a social and economic disaster, whereas the same incident might have far less serious consequences if sensible protection against the unexpected were in place.

Thus, two pressing problem areas were outlined, with pointers for where to look for solutions. Professor Lama suggested that the Himalayan Future Forum continue to push this agenda.

A Stress Multiplier

While carbon emissions are one of the factors driving global warming, carbon credit trading, regulated under the Paris Agreement (2015), helps reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The goal of the carbon credit system is to provide a financial incentive to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The Environment Protection Act (2019) provides a mechanism that secures the government a royalty for granted sequestration rights. However, carbon sequestration in Nepal is complex because the area per harvestable plot is small and the administrative process is cumbersome. The best strategy would be to focus on high-quality carbon only, as the market price is higher and would yield greater compensation.

The seriousness of the looming ‘cryosphere disaster’ in the Himalayan climate change debate was once again underscored by Sudan Bikash Maharjan of the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

His alarming presentation focused on the region’s role as a ‘water tower’ for 240 million people in the Hindu Kush Himalaya Region (HKHR). Not long ago, enormous quantities of water were safely stored in the glaciers, to be released slowly in amounts the river system could digest.

The Yala Glacier (in the featured photo), for example, has nearly vanished over the past half-century: 66% of its ice mass has melted, and all that water is running downhill uncontrollably.

The locals are faced with seemingly conflicting phenomena, over-the-top precipitation or merciless drought, as Sonia Awale (Nepali Times) remarked: “There is either too much or not enough water”.

More reliable data would deepen insight into how the landscape is changing, reinforce decision-making, and facilitate an adequate emergency response.

Maharjan used the term ‘water bankruptcy’ to signal how dire the situation is. We may have passed the point at which this worst-case scenario can be reversed. But before we come to that conclusion, there are still measures that may prevent unnecessary drama, like ‘remote sensing’ technology and state-of-the-art weather forecasting.

Climate change is a stress multiplier that makes life in higher habitats increasingly difficult. To reverse these dynamics is beyond the locals’ power, however resilient they are. Maharjan: “Reconstruction is also a political process”.

Sounds of Hope

However dark the situation may seem, there were also sounds of hope and a dedication to preserving or creating pleasant living conditions in the very areas now under stress.

Rahul Bhushan is an eco-architect who builds ‘infrastructure for the future’ based on the ancient Kath Kuni architecture: “a time-honoured construction technique that intertwines the natural elements of the region into a seamless mix of durability and grace”.

Together with like-minded souls, he founded a collective, The NORTH, in Naggar, Himachal Pradesh, to experiment with a holistic approach to architecture and an eco-friendly way of life that is compatible with the surrounding landscape and the local population.

Adaptation, according to Bhushan, is also a way to think about addressing problems: “Where and how will we build new places to live?”

Another ‘hill’ that needs attention is the rapid growth of digital technology, which was at the centre of Nitin Pai’s presentation, the co-founder and director of the Takshashila Institution, an independent centre for research and education in public policy.

He addressed the deep challenges posed by the concentration of all-important personal and demographic data in the hands of a handful of information technology moguls, who seem to use their power primarily for economic gain.

His crisp and engaging presentation was enlightening, warning about the negative aspects of this development and outlining countermeasures to cushion or even overcome the IT dominance many fear. Reverting to open-source technology is one way to counter the dominance of closed software systems. He also referred to Susie Alegre’s book ‘Freedom to Think’ and said that Nepal can be “a bridge where communities come together”.

His crisp and engaging presentation was enlightening, warning about the negative aspects of this development and outlining countermeasures to cushion or even overcome the IT dominance many fear. Reverting to open-source technology is one way to counter the dominance of closed software systems. He also referred to Susie Alegre’s book ‘Freedom to Think’ and said that Nepal can be “a bridge where communities come together”.

Learning and Earning

With four or five million non-resident Nepalis living and working abroad, and many more still leaving the country in droves, around 2000 individuals per day(!), economic migration is a two-faced phenomenon.

Social researcher Anita Ghimire observes a shift in the rational and emotional approach: aspiring youngsters are now moving to ‘learning and earning,’ whereas those leaving Nepal previously did so to get low-pay unskilled work.

In a sense, the resulting brain drain is unsettling, but some argue that being a successful migrant may be preferable to scrambling for a decent job at home.

Writer/journalist Ramesh Bhushal interpreted the notion of migration in his own way by walking from Tibet to India and wrote a book about it — “Chhalbato: Kailash Dekhi Ganga Samma”—a travelogue covering over 2000 kilometers from China (Tibet) to India along the Karnali River. For him, climate change is a reason to seek opportunities. “It triggered wanderlust in me.” As a result, he found his niche in professional writing under the aegis of the Earth Journalism Network.

Where Bhushal examines migration at a micro level, Giuseppe Savino, a labour migration consultant specialising in the financial and development aspects of economic migration, takes a macro view, considering how countries of origin address the phenomenon. For example, India, China, and the Philippines “export skills”, while Pakistan and Bangladesh see unskilled labour flee the country. Nepal hovers somewhere between those extremes.

From the perspective of the receiving destination, the influx of foreign labour capacity is often directly linked to a shrinking workforce. European countries such as Cyprus, Romania, and Portugal absorb large numbers of Nepali migrants, both skilled and unskilled. Seventeen EU countries have signed labour agreements with labour supply sources, offering relatively highwages, good working conditions, and better education for children.

While leaving your country is difficult, returning home may be tricky as well. Anita Ghimire: “People often love the network they have built in their new country, and the folks back home may not accept new skills or altered behaviour”. By contrast, the rich diversity of populations in the Himalayan range may help with reintegration. Another hurdle to returning is that most children born abroad do not consider Nepal ‘home’ as their parents do.

Then there is a third dimension, from Nepal’s GDP perspective, since around 25% of the country’s national income is coming from remittances, that is, money sent home by migrants mostly to support their families. “The generation dividend is diminishing’, warns Savino. “This country has to understand how to benefit from remittances”.

Performance is More Important than Provenance

The third-to-last panel focused on marketing products from the Himalayas, such as Nepali tea.

Proper branding enables local products to be sold in distant markets without intermediaries, who often skim off profits for their own benefit, leaving the Nepali producer or supplier with only a fraction of their products’ true market value.

But realising an effective branding strategy is not that easy and has more to do with entrepreneurial skills than with authenticity or domestic roots.

The gist, according to Navroze Dhondy (Creatigies), is that “performance is more important than provenance”. While many entrepreneurs focus more on local aspects, foreign markets are much more interested in the products’ qualities.

“You must see actionable opportunities”, said Upendra Singh Thakur, “and suppress the eagerness that is typical for many entrepreneurs. Do your homework, begin local, and then go global”.

Branding is not so much about emotion as about long-term commitment, brand personality and brand consistency. “There may be a gap in the market,” added Dhondy, “but is there a market in the gap?”

From Heritage to Hardware

The world has 7100 languages (!), and Nepal is highly multilingual, with 129 spoken languages, 24 of which are endangered. Think of Magar, Chepang, Bhasa, and Newa.

Linguists and IT specialists work to preserve languages that are vanishing for various reasons, because revitalisation is often not an option. Automated translation is part and parcel in this area, but not without challenges.

Marie Caroline Pons introduced this topic, arguing that the ambiguity of language in general creates a range of issues in this field. Small nuances in tone can convey a completely different meaning, making it very difficult to build translation models for spoken language that are suitable for use in an IT environment.

Language embodies identity, even if we do not always realise this. If a language ‘dies’, a whole lot of indigenous cultural value disappears, verbal history, spoken narratives, literature, tales, jargon, folklore, vernacular.

From heritage to hardware: digital storage may be the best method to keep such languages at our fingertips, so they can be revived, albeit artificially, when needed.

Smaller Alliances

Thibault Danjou (Augusta, Phitrust) appreciates the countries in the Himalaya region for their limited size. “Things work faster; you see results sooner”. As a trend economist, he is interested in the possibility of applying Singapore’s very successful model in other countries in the region. “How can we help them to boost their economies as well?”

National branding can help, but it is even more complex than product branding. For example, the Bhutanese concept of Gross National Happiness, which helped put Bhutan on the map, emerged spontaneously without any marketing expertise fuelling it.

Apekshya Shah (Tribhuvan University) believes that competition and cooperation can coexist if neighbouring countries have solid domestic foundations.

In Tariq Karim’s vision, water and energy security are essential for the entire region. “We can’t survive alone.” The abundance of clean energy potential is a gift from above, if only the Himalayan states can unwrap it together.

“Colonial powers disappeared, but were replaced by superpowers, which behave exactly the same”. Smaller countries simply must flock together in South Asia to survive. Economic cooperation around the Bay of Bengal would be great.

Former EU ambassador Rensje Teerink, who served in Nepal and Bangladesh, hopes for a revival of regional integration. Initiatives such as SAARC and SAFTA offered hope, and a ‘reductionist approach’ may well rekindle that spirit if local politicians pursue smaller alliances. Teerink sees a welcome signal that such alliances are achievable in the recent trade agreement between India and the EU. “Davos was an eye-opener. The Canadian PM Carney is right. The middle powers must join forces.”

Sujeev Shakya (Nepal Economic Forum), while closing the day, noted that “Nepal has not been able to leverage the goodwill it has”. Apekshya Shah tuned in, saying that “Nepal must signal that it can manage external competition. We must work on a clear political image. Development is the strongest asset in the geopolitical arena. There is space for dialogue in Southeast Asia. But we must get our house in order”.

About the author

Barend Toet is the founder and editor-in-chief at Nepal Connect. He is a well-known Dutch publisher and writer. Editorial product development is his forte. In his younger years, he was the driving force behind successful niche publications across a wide range of fields, including pop music, private investing, and chess. Later in his career, he ‘recycled’ magazine content as an innovative agent, marketing text and imagery, and wrote numerous magazine articles and several books.

Toet visited Nepal in the early 1980s and has returned some fifty times. He is also a board member of the Dutch Nepal Federation (NFN) and wrote a crime novel set partly in Nepal, The Kathmandu Complot (1982).

Useful Websites and Sources

HFF: https://www.himalayanfutureforum.org

ICIMOD: https://www.icimod.org

The NORTH: https://thenorth.in/architecture